NYC, 2am, 1990-something. A Ford Bronco drives through the still bustling streets with its windows down and a bunch of rowdy revelers inside singing loudly along with the blasting reggae music.

I am living while I am living to the father I will pray

Only him knows how we get through every day

With all the hike in the price

Arm and leg we have to pay

While our leaders play…

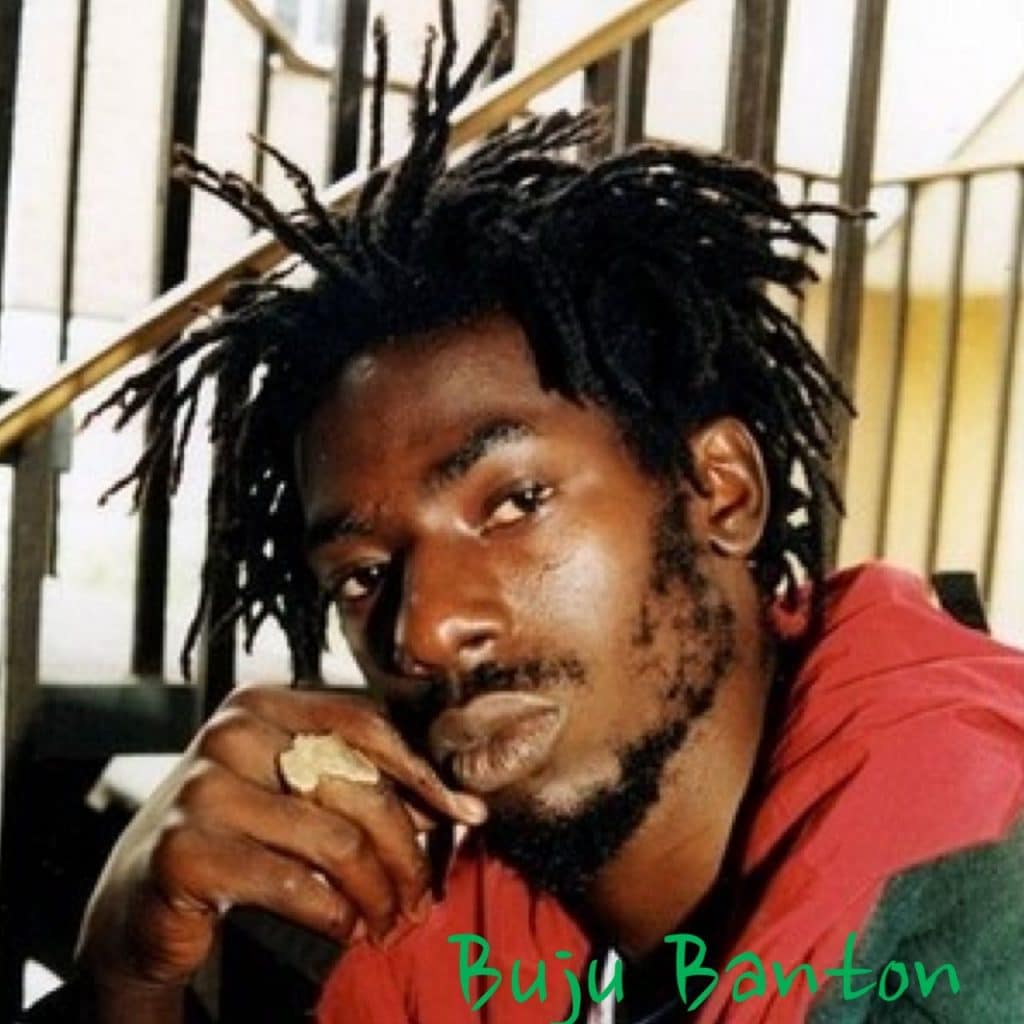

The music is Buju Banton’s ‘Til Shiloh album and the revelers are my friends and I. Whenever I listen to that album nowadays, that vague, random memory comes to mind, a recollection which doesn’t recall a specific moment, but rather an amalgam of trips into and out of the city going to and coming from numerous reggae shows during my 20s.

My love for reggae music started during my teenage years in the late 80s immediately after being introduced to the classic roots music of Bob Marley and Peter Tosh. Driven to learn more about the origin of this unique sound and the meaning and context of the lyrical messages it contained, I eagerly began a journey of discovery. Synchronistically, the universe guided me by bringing me to Jamaica (with no planning on my own part) and subsequently providing me with several key mentors. As if on demand, I uncovered opportunities to reason with Jamaican people, reggae aficionados and reggae artists themselves. Along with my own research, these interactions boosted my vocabulary of patois and understanding of its colloquialisms and taught me about the history of Jamaica and Rastafari, and the nuances of their cultures. All of this served only to deepen my passion for reggae music.

With this increased knowledge, my love for roots reggae would branch out to include the many sounds of Jamaican Music, including ska, dub, lovers rock and dancehall.

Admittedly, however, I had mixed feelings about the latter. I dug its earliest incarnations and the music released throughout the 70s and most of the 80s, but I flat-out disliked most of the current dancehall sounds of the 90s. The music had become almost exclusively digitized and with rapid-fire, often slack (vulgar/crude) vocals, the modern dancehall simply did not resonate with me. I wanted to like it, but except for a few tracks here and there, I just couldn’t get into it.

Then, in 1995, Buju Banton released ‘Til Shiloh.

At the time, Buju had risen to prominence based on several successful singles and albums, including Mr. Mention, which upon its release in 1992, had become the best-selling album in Jamaican history. That same year, he had broken the Jamaican record for most #1 singles which had been previously held by a guy named Bob Marley.

Up to that point, I was not a fan of Buju, but ‘Til Shiloh seemingly came out of nowhere to blow me away and become one of my most-listened to and cherished reggae albums of the 1990s.

‘Til Shiloh not only marked a major change in Buju’s career, catapulting him to international stardom, but it also proved to be a landmark album that turned modern dancehall on its head by stripping the computerization in favor of a more organic, soulful sound, using real instrumentation and integrating African rhythms. While a few tracks still maintained that homogenous sound popular at the time, the juxtaposition of dancehall toasting over acoustic guitar, roots riddims and Nyabinghi drums and chants breathed fresh life into a subgenre that had become predictable and mundane.

Lyrically, while Buju’s recent adoption of Rastafarinism had already begun to inspire a slight shift in content when compared to his previous album, on ‘Til Shiloh, Buju’s writing admonished, rather than glorified, the banal and profane subjects of gang and gun violence, sex and bling. On the contrary, his songs expressed ancestral pride while promoting self-worth, unity and magnanimity.

Whether it can be attributed to his Rastafarian practices, simple maturity or most likely a combination of both, like roots reggae predecessors, Buju sings with social consciousness, becoming a voice of the sufferah.

In “How Could You”, over a re-cut version of The Bassies’ classic “Things A Come Up To Bump” riddim, Buju sings:

Being oppressed by the oppressors, all different types of stress

For the sorrows of the poor, they don’t even care less

Refuse to deal with world atrocities, civil unrest

Instead they’re building penitentiaries as big as a bird’s nest

Saying we are to be blamed for whatever what mess

In “Untold Stories” he sings:

What is to stop the youths from get out of control

Full up of education yet no on no payroll

The clothes on my back have countless eyehole

Could go on and on and the full has never been told

Though this life keep getting me down

Don’t give up now

Got to survive somehow

Rather than songs that objectified women, Buju wrote amazing lyrics like these from “Wanna Be Loved:”

Been searching a long long time

For that oh-so-true love

To comfort this heart of mine

No pretense stop wasting my time

A virtuous woman is really hard to find

I’m telling you lady

I’m only human, not looking for impossibility

Just a genuine woman with sincerity

Someone who is always near to hold me

Show me you care, up front and boldly

While I did not necessarily identify with Buju’s messages from firsthand experience, nevertheless I could certainly appreciate his sentiments as I was awakened enough to understand the disparity in society and be grateful for the blessings that life had bestowed upon me. I have enough empathy to ally with the less fortunate, and I have always admired those who stick up for others and rally the downtrodden. This defining characteristic of reggae music has always appealed to me; it’s what drew me in and kept me here all these years.

I can’t remember all that much from most of my 20s, but something I know for certain – ‘Til Shiloh was a big part of it. It’s an album that will forever remain among my favorites.

[gravityform id=”131″ title=”false” description=”true”]