On October 22nd, 2021, VP Records reissues Keith Hudson’s obscure and edgy masterpiece, Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood on vinyl and CD, and for the first time, on digital streaming platforms. The recent passing of the massively influential and well-known producer Lee “Scratch” Perry is the perfect time to reflect on his most comparable peer, Keith Hudson, who died before his time in 1984 but with a wildly creative legacy during reggae’s golden era. Both men, Scratch and Hudson, aspired to be singers but ultimately excelled as album and song producers, not afraid to defy convention in search of artistic epiphanies.

In Jamaica, Hudson was known briefly for his standout hit record with Big Youth, “Ace Niney Skank” and his debut production with singer Ken Boothe “Old Fashioned Way.” From there Hudson’s output maximized the use of remix and versions that were the hallmark of early dancehall and soundsystem culture. Multiple iterations of songs appeared across releases, notably including Delroy Wilson’s adaptation of the standard “House Of The Rising Sun,” reimagined as “Place In Africa.” This track utilized a heavy, droning rock guitar power chords that were totally outside the mainstream reggae aesthetic at the time.

Hudson’s most enduring catalog album is once-obscure Pick A Dub, revived by the Blood & Fire label and reissued by VP and his signature vocal album Rasta Communication. Hudson would continue his sonic experimentation into the 80s with psychedelic use synthesizer on tracks such as “Nuh Skin Up.” In the process, his work caught the attention of members of Joy Division, and his “Turn The Heater On” was covered by New Order during one of their early Peel Sessions. An overview of Hudson’s catalog can be found here. His original independently pressed vinyl releases are still highly coveted and can be found on his labels including Mafia, Imbidimts, Disc Disk, Rebind, Mamba, and Joint International.

Below are Hudson biographer (and superfan) Vincent Ellis’ meticulous liner notes for VP’s edition Flesh Of My Skin, published here for the first time for additional context and insight. The mystical and tortured sound of Keith Hudson was described in a 2004 Pitchfork review of this album as “eternally black roots … and the worms that writhe in the mud of the shared mind.” Dig in below and find out what they were talking about.

–Carter Van Pelt

…

“Singer, producer, songwriter Keith Hudson is soon to release his fourth album on his own Imbidimts label. The album is entitled ‘Black Breast Has Produced Her Best’ and will also be released in London.”

This minor entry in the Merry-Go-Round column of The Jamaica Daily Gleaner in August of 1974 by entertainment and arts writer Balford Henry was the only announcement of Keith Hudson’s Flesh Of My Skin LP prior to its release. Even then, the label and the title were incorrect, and the timing of the release was wrong, as the album would be released a full year later in Jamaica, after its initial run in the UK on the Mamba label. Perhaps this oversight was due to Balford Henry having grown weary of his  association with Keith Hudson. The journalist and the record producer had actually been partners in a record label for the past year, called Hudford Records, a combination of their first and last names. They released a series of short-run singles that did very little business. Balford was done with producing by the time he wrote this notice, while Keith Hudson was close to financial collapse before his forthcoming trip to England to finish Flesh Of My Skin, a trip that would make or break his career.

association with Keith Hudson. The journalist and the record producer had actually been partners in a record label for the past year, called Hudford Records, a combination of their first and last names. They released a series of short-run singles that did very little business. Balford was done with producing by the time he wrote this notice, while Keith Hudson was close to financial collapse before his forthcoming trip to England to finish Flesh Of My Skin, a trip that would make or break his career.

Having emerged in the late sixties as part of the entrepreneur-turned-record-producer wave as studios and pressing plants became more numerous on the island, Keith Hudson, who ran a dental lab, scored a hit with his very first tune at the age of 23. “Old Fashioned Way,” produced by Hudson and sung by Ken Boothe, shot up the Jamaican charts in 1969, and soon Keith was producing other artists like Delroy Wilson and John Holt, before moving on to the DJ craze he helped create with toasters like U Roy, Dennis Alcapone and Big Youth. His ‘S90 Skank’ with Big Youth was a monster hit, and his take on Hugh Masekela’s ‘Riot’ by Soul Syndicate stayed on the charts for several months in 1972. The financial success of these singles would offset some of the personal and professional damage Keith suffered following a home invasion in 1972 by rival factions of the PNP and JLP political parties. Sometimes referred to as The Mall Road Incident, this event would change Hudson’s future plans, as the studio he was building at 24 Cassia Crescent was left in ruins. Deliberately moving into a small 2nd-floor office space at 127 King Street, Keith was fortunately and knowingly sharing the same building with a popular group called The Wailers, with lead singer Bob Marley having his Tuff Gong Store on the 1st floor. All Keith had to do was keep the lights out at night so the landlord didn’t know he was living there as well. He would turn this experience into a song called ‘I Won’t Compromise’ on the Rasta Communication LP.

127 King Street was a hub of activity, as a lot of musicians would congregate there, and reporters would make it a regular stop. As Bob Marley began to grow in importance, it became the first place to go if you were interested in the story of the day on reggae music. Keith took full advantage of this, befriending Balford Henry, who popped in one day to do a story on The Wailers, and, having found Bob not there, a usual occurrence, he was persuaded by Hudson to become a partner in the record business. In exchange for his help in financing the records, Balford would get producing credit and have access to a lot of musicians he hoped to utilize in the future when he established his own label. This was 1973, somewhat of a down year for Hudson, as while his Mafia label was holding its own with a couple of hits by Alton Ellis, his first three albums went nowhere, as the local scene was not ready for Hudson’s unique vocal stylings and twisted but passionate lyrical content. Keenly aware of the Wailers’ growing European acclaim as a result of the London backed Catch a Fire sessions, Keith was making plans to go international.

He met Jean Fletcher in 1970, 16 years old, born in Ocho Rios but living in the States from childhood, while she was visiting relatives in Jamaica. He fell in love immediately, and would visit her in Philadelphia when he started his semi-annual sojourns to New York and London on a regular basis starting in 1970. They married in January of 1973, in Kingston, with the hope of Keith getting his green card and moving to the States to join her at some point. Not one to limit his love, he met a woman named Beverley in London in the fall of 1972, and a teenager named Petrina at his shop in Kingston and fathered children out of wedlock with each of them in 1973 and 1974, respectively.

Flying to London in September of 1974 with only £1,200, leaving several of the expenses of the now defunct Hudford Records to fall on Balford Henry, Keith stayed for a time with Beverley and their little boy, Barry, in the Kilburn area of Northwest London. He needed contacts in the local music scene, and so reunited with his childhood friend, coincidentally named Barry, aka Militant Barry, who was trying to establish himself as a producer and DJ in England. Barry remembers “‘Flesh of My Skin’ represented a new chapter for Keith, he was turning the page, pushing himself as an artist as opposed to producing others.”

He also met Bunny McKenzie, a guitar player born of Guyanese parents, who was a well-known session player to visiting artists. “Keith’s thing was special, very creative. Keith liked the blues element in my playing. We met when he came to England and he told me about his concepts. I loved working with Keith, he gave me a lot of creative freedom. He wanted my input, not a robot (laughing).”

Keith’s concepts for the album were far more ambitious than anything else he had done to date. Having been exposed to the writings of Frantz Fanon on an earlier visit to England, the French West Indian political philosopher would have a profound influence on Keith’s lyrics. Fanon’s writings dealt with the effects of colonialism and the need for black liberation, emotionally, spiritually and even through armed revolution if necessary. Several thought processes from Fanon’s seminal work ‘Black Skin, White Masks’ can be heard in the lyrics of Keith’s ‘Flesh of My Skin’ LP. Keith married these ideas to his own call for African-Caribbean awareness, with an emphasis on motherhood and matriarchy; a tribute to the five women in his life, his mother Ruth, his wife Jean, his former partner Norma, who was mother to three of his children, and to his two baby mamas, Beverley and Petrina.

Keith brought with him from Jamaica the backing tracks, mostly Soul Syndicate sessions, recorded at Dynamic Studios and Harry J. Studios in Kingston. These were on reel-to-reel tape and consisted of the rhythm tracks, and perhaps more, depending on the circumstance. One such circumstance was the first track on the album, called “Hunting.” As opposed to the usual trap drums set, Keith hired Count Ossie and the Mystic Revelation to perform their nyabinghi style of hand drumming. This evocative instrumental sets the tone for the LP, a sense of menace and excitement at the same time, but two of its key components happened by chance.

Balford remembers, “I met this guy who came by the office one day, this guy who had a whistle sound, a bird sound, and we went to the studio where Keith was working on a version of ‘I Broke The Comb’ with the Barrett Brothers, Carly and Aston. He did the whistling sound and Keith stopped the session and went and got the “Hunting” rhythm track, because he wanted it on that. He whistled on top of the rhythm, it sounded real nice, but Carly felt the track needed something else. Carly went outside and grabbed some leaves and branches and crunched and cracked them on the studio floor, and that sounded like someone or something trekking through the jungle.”

For overdubbing, Barry recommended Chalk Farm Studios in London, a hot spot for expatriates and visiting Jamaican artists. Run by Vic Keary, whose tube amp gear gave the studio its signature sound. Chalk Farm engineered some of the top singles on the UK reggae charts, including Bob and Marcia’s “Young, Gifted, and Black.” Engineer Neil Richmond was 25 when he worked on Flesh Of My Skin. He started at Chalk Farm when he was 21.

“Hudson’s way of recording wasn’t like anybody else’s, you weren’t sure what was the head and what was the tail, if you know what I mean. He knew what he was doing, which is all I needed to know as the engineer. Musicians came in at different times, and when they came, we would just jump over and Keith would say we’ll do that part now. It was a bit chaotic. Keith knew how to manage it, he just didn’t divulge the information with us.”

A lot of musicians made guest appearances on Flesh Of My Skin, including on guitar Delroy Washington, Buster Pearson and John Kpiaye. Bunny McKenzie recognizes his distinct sound on three of the tracks, “That twangy guitar sound, on ‘Flesh Of My Skin’, ‘Fight Your Revolution’, and ‘Talk Some Sense,’ that’s me.”

Keith talked about how he chose musicians with Carl Gayle in an interview for Black Music magazine soon after the album’s release:

“I always have to search for a new music. Find a way to identify my sound by seeking unknown musicians, musicians not so popular. So if he does a sound for me I can have that sound for a good while before anyone else has a sound like that. This guy named Tony played organ on “Hunting.” He’s with a band called The Titans. But that’s how I do it. Go ‘round and take out all the best players.”

For keyboards and synthesizer, Vic Keary recommended Ken Elliot, who was Chalk Farm’s go to guy for keyboard and synth overdubs, having been part of the Chalk Farm house band called 7th Wave.

“Keith didn’t have a lot of money, but he was very persuasive, and I would try to help out as much as possible as I was into the music. He had epic themes, the way his music was, it was heavy. When you try to do something new, producers tend to discourage it. Keith liked you doing something different, he didn’t want you to do what everybody else was doing. I don’t think he was crazy, some people thought he was, he was just a bit mad, a bit of a mad genius. In the studio, he kinda conducted you, egged you on and encouraged you while you were playing, pushed you towards what he wanted, very animated. I never really understood what he was doing, all I knew is, he went into the music with a great deal of passion. Keith was a loner, a man with a mission.”

Since the album focused heavily on the role of the black woman and mother as a source of strength, Keith wanted a powerful female vocalist to accompany him on the album. Bunny Mckenzie: “Keith told me he needed a strong woman vocalist on the album, and I recommended my sister Candi, told him she was a wicked vocalist.”

Twenty-one year old Candi McKenzie was just starting out as a professional singer. She had done a little session work for Bob Marley at Island, she and her cousin Yvonne did the backing vocals to the studio cut of “No Woman, No Cry.” She had lost her parents and her husband when she was eighteen in a family tragedy that would scar her forever and lead to her accidental overdose in 2003. Her work with Hudson is some of her finest material, you can feel the pain in her voice, in her singing, on every track. Bunny: “He gave my sister a lot of room to express herself, Candi had a way of overpowering some leads, it could intimidate other vocalists, but Keith wanted that.” Candi and her brother would go on to do work with Aswad, and Candi cut a disappointing LP with Lee Perry in 1977 that sat on the shelf for years due to a dispute between Chris Blackwell and Lee Perry, before being released in 2011. She put out a handful of disco singles in the 80’s, but nothing comes close to matching her majestic singing on Flesh Of My Skin.

The album was recorded in a relatively short period of time, long nights with little sleep. Driving home early one morning after an all-nighter, Keith had an inspiration – one born of necessity. Balford, “Keith noticed that early in the morning the milkman would leave the milk and the bread on the front porch at a lot of the houses. He would stop off and steal it. It was his food for the day, he didn’t have money, and that’s how he survived when he got to England. He had a very rough life, and he felt the only way to survive was to do things like that, do whatever is necessary to survive.”

The album was recorded in a relatively short period of time, long nights with little sleep. Driving home early one morning after an all-nighter, Keith had an inspiration – one born of necessity. Balford, “Keith noticed that early in the morning the milkman would leave the milk and the bread on the front porch at a lot of the houses. He would stop off and steal it. It was his food for the day, he didn’t have money, and that’s how he survived when he got to England. He had a very rough life, and he felt the only way to survive was to do things like that, do whatever is necessary to survive.”

The Black Breast Has Produced Her Best, Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood is the full title on the album’s front and back covers, more of a poem or aphorism than an actual title. The original LP had twelve tracks on it. The aforementioned “Hunting,” followed by “Flesh of My Skin.” “If only you were like my brother, who sucked the black breast of my mother, flesh of my skin, blood of my blood…”, a beautiful song on motherhood and the passage of time. This is followed by the dub version called “Blood Of My Blood.”

“Testing Of My Faith” finds Keith reflecting on the black experience in the West Indies, from the perspective of a man trying to hold onto his faith; “And I can’t hold back these anxieties.” Fight Your Revolution is a call to arms, spiritually or physically, as he ponders the question, “maybe today, maybe tomorrow … what you scared of … struggle, struggle.” It’s this mix of subtlety and directness that powers so much of the album, married to heavy rhythms and the piercing backing vocals of Candi McKenzie. “Darkest Night” is a bit of an outlier on the album, thematically, as it was released a year earlier on the UK Spur label and is based on an adventurous night in London where Keith was driving around the outskirts of the city and got lost. Keith pulls it into the world of ‘Flesh Of My Skin’ with all new vocals that emphasize the sense of dread, and this track benefits strongly from Candi’s backing, which was not on the original.

“Talk Some Sense” uses the rhythm Keith created for his third album’s title track, “Class and Subject,” an album-only cut available on pre-release from 1973. Like much of the Flesh Of My Skin album, the lyrics on “Talk Some Sense” are diffuse in meaning, this one an allusion to a difficult relationship, but deliberately undefined so it applies to one or all “occasion(s)” as referenced in the song. “Treasures Of The World” is a parable in poetic form, of man seeking treasures outside while Keith seeks his inside himself. “My Nocturne” is the dub of “Treasures Of The World.” The next track is truly a revelation, as at first glance it seems a straight up adaption of Bob Dylan’s prison classic “I Shall Be Released.” But Keith drops all references to incarceration with two key line changes. “So I remember every face of every man who put me here” becomes, “So I remember every face of every man who brought me here.” Then, “Yet I swear I see my reflection, somewhere so high above this wall” becomes, “But I swear I see my reflection, somehow, somewhere it’s got to be there.” It’s these subtle but significant changes that put the song directly in line with the rest of the album, as it becomes the story of a slave reclaiming his identity. “No Friend Of Mine” finds Keith speaking directly to someone whose duplicity has ruined many lives, but one day….

“Stabilizer” closes the album, a soaring instrumental on Hudson’s “Peter and Judas” rhythm, with Augustus Pablo on melodica and Leroy Sibbles of The Heptones on bass.

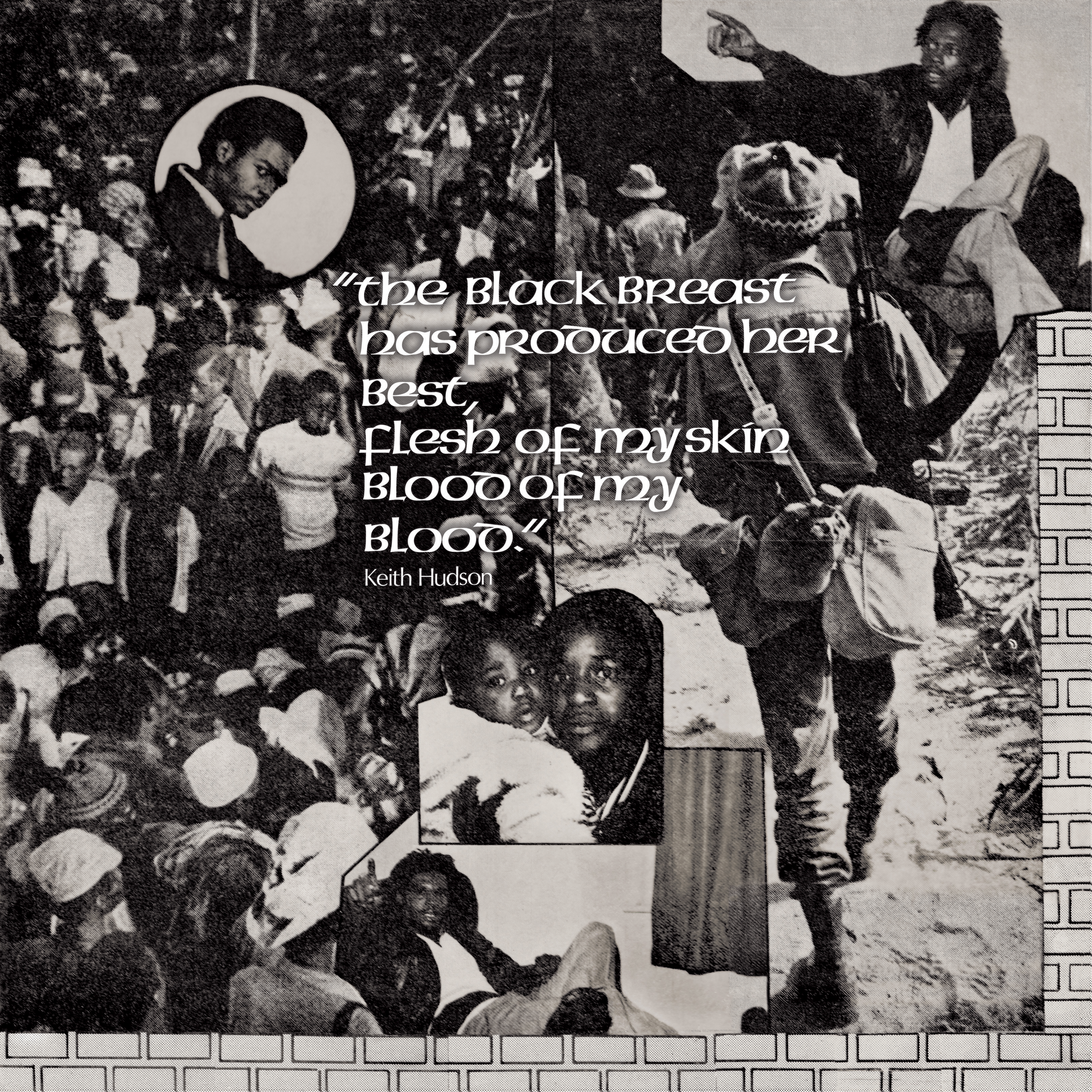

The sense of purpose displayed on the music is carried over to the album’s cover. Militant Barry took a couple of pictures of Keith on the couch in Beverly’s flat, pointing with his finger in opposite directions, for the bottom and top right of the LP. He cut out newspaper pictures of soldiers on patrol, and one of a refugee camp, and used a partial picture of his head surveying the scenes. At the center, he put a picture of Beverly with their son Barry, when he was an infant, a clear reference to the theme of motherhood. Keith duplicates the front cover on the back, but adds a dense poem on the back cover on the struggle for freedom, written with words drawn from Jamaican patois, scientific terminology, and various Middle English phrases. Keith was fascinated by the meaning of words and objects and would spend hours reading the dictionary.

With the album complete Keith set about releasing it. He set up a mail order capability with Richards Records, a London based distributor who advertised in local magazines. He and Barry visited with all the record shops in the area, establishing a connection with local vendors. He visited the reggae nightclubs where, writer Saba Saakana remembers: “Flesh Of My Skin was a great underground hit, when they heard the rhythms in the community clubs, they went wild, sky high!! He was a gifted songwriter and musically, he could put tougher a rhythm nobody could top, even Bob Marley wasn’t doing that kinda thing.”

Chris Lane in Blues And Soul called it “one of the best albums to be released this year, it combines strong, heavy rhythms with strong, heavy lyrics.” Carl Gayle wrote in Black Music magazine, “Buy this album. It is the most moving, satisfying piece of Jamaican music I’ve heard since Catch A Fire and surpasses that album. The music here is disturbing, truly evocative. This is the album of the year without a doubt.” Let It Rock magazine said Flesh Of My Skin is the most potent reggae performance in a long, long while, a remarkable piece of music.”

David Rodigan, the legendary DJ, who conducted the only radio interview with Keith in 1978, remembers the impact the album had upon him on its release:

“I remember we got the Sgt. Pepper album in the summer of 1967, and we spent all night listening to it, me and my friends. And I remember getting the Flesh Of My Skin album in the Winter of ‘75, and seeing that cover, and seeing that sleeve for the 1st time, and I sat and I kept staring at it with the soldiers and the mother with the child in its arms, and that photograph of him in a profile, and me trying to figure out who all these other people were, and why are they on the sleeve? There is a haunting, mystical quality to it, it’s definitely in a realm of its own, with its eccentric vocals and rhythmic structure.”

The LP was a big success for Keith Hudson and allowed him to forge a creative path forward into the rest of the decade and into the ‘80s before his untimely death in 1984. As Balford Henry would write in The Daily Gleaner upon finally hearing the album in 1975: “The album proves just how much can be done for Jamaican music, the album took a year to make, not every producer should spend so long making albums, but it shows that this producer felt it important enough, so that he could add the spice necessary to make it all blend.”

This album is taken from the original 1974 release. There was a reissue in 1988 on Atra, that was reissued in 2003 on the Basic Replay label. These earlier reissues had a slightly different mix, using the no longer existing two-track master, not as clean as the original tube-amp mix from Chalk Farm Studios. This album features bonus tracks, including the Count Ossie backing track to “Hunting,” the original dub to “Darkest Night,” and a Syd Bucknor-created dub from 1988 for “Talk Some Sense.”

Vincent C. Ellis, March 2021

Vincent C. Ellis is a writer and filmmaker and the author of Keith Hudson, An Illustrated Discography

He is currently working on a biography: Black Morphology, The Life And Music of Keith Hudson